Two major groups of chloroplast DNA haplotypes in diploid and tetraploid Aconitum subgen. Aconitum (Ranunculaceae) in the Carpathians

Abstract

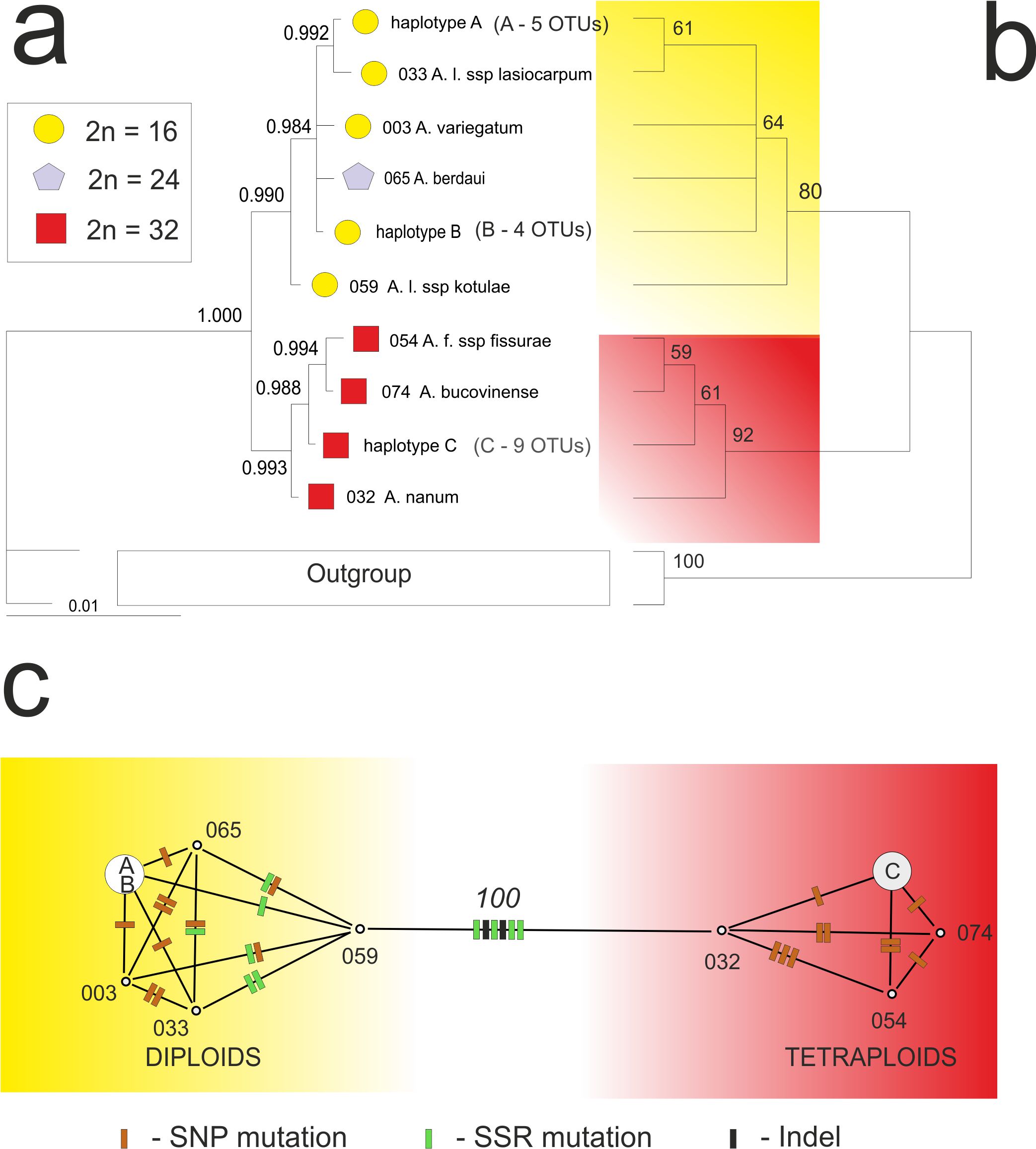

Aconitum in Europe is represented by ca. 10% of the total number of species and the Carpathian Mts. are the center of the genus variability in the subcontinent. We studied the chloroplast DNA intergenic spacer trnL(UAG)-rpl32-ndhF (cpDNA) variability of the Aconitum subgen. Aconitum in the Carpathians: diploids (2n=16, sect. Cammarum), tetraploids (2n=32, sect. Aconitum) and triploids (2n=24, nothosect. Acomarum). Altogether 25 Aconitum accessions representing the whole taxonomic variability of the subgenus were sequenced and subjected to phylogenetic analyses. Both parsimony, Bayesian and character network analyses showed the two distinct types of the cpDNA chloroplast, one typical of the diploid and the second of the tetraploid groups. Some specimens had identical cpDNA sequences (haplotypes) and scattered across the whole mountain arch. In the sect. Aconitum 9 specimens shared one haplotype, while in the sect. Camarum one haplotype represents 4 accessions and the second – 5 accessions. The diploids and tetraploids were diverged by 6 mutations, while the intrasectional variability amounted maximally to 3 polymorphisms. Taking into consideration different types of cpDNA haplotypes and ecological profiles of the sections (tetraploids – high‑mountain species, diploids – species from forest montane belt) we speculate on the different and independent history of the sections in the Carpathians.

References

Cain S.A. 1974. Foundations of plant geography. Hafner Press, London.

Deng T., Nie Z.-L., Drew B.T., Volis S., Kim C., Xiang C.-L., Zhang J.-W., Wang Y.-H., Sun H. 2015. Does the Arcto-Tertiary biogeographic hypothesis explain the disjunct distribution of Northern Hemisphere herbaceous plants? The case of Meehania (Lamiaceae). PLoS ONE 10 (2): e0117171. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0117171.

Dwivedi B, Gadagkar S.R. 2009. Phylogenetic inference under varying proportions of indel induced alignment gaps. BMC Evol. Biol. 9: 211.

Farris J.S. 1989a. The retention index and homoplasy excess. Syst. Zool. 38: 406–407.

Farris J.S. 1989b. The retention index and rescaled consistency index. Cladistics 5: 417–419.

Felsenstein J. 2004. Inferring phylogenies. Sinauer Associates, Inc., Sunderland, Massachusetts.

Fergusson C.J., Krämer F., Jansen R.K. 1999. Relationships of eastern North American Phlox (Polemoniaceae) based on ITS sequence data. Syst. Bot. 24: 616–631.

Gawal N. J., Jarret R. L. 1991. A modified CTAB DNA extraction procedure for Musa and Ipomea. Plant Mol. Biol. Rep. 9: 262–266.

Götz E. 1967. Die Aconitum variegatum-Gruppe und ihre Bastarde in Europa. Feddes Repert. 76 (1-2): 1–62.

Huelsenbeck J.P., Ronquist F. 2001. MrBayes: Bayesian inference of phylogenetic trees. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 17: 754–755.

Hultén E. 1937. Outline of the history of arctic and boreal biota during the Quarternary period: their evolution during and after the glacial period as indicated by the equiformal progressive areas of present plant species. Thule, Stockholm.

Husband B. C. 2004. The role of triploid hybrids in the evolutionary dynamics of mixed-ploidy populations. Biol. J. Linn. Soc. 82 (4): 537–546.

Huson D.H., Bryant D. 2006. Application of phylogenetic networks in evolutionary studies. Mol. Biol. Evol. 23 (2): 254–267.

Ilnicki T., Mitka J. 2009. Chromosome numbers in Aconitum sect. Aconitum (Ranunculaceae) from the Carpathians. Caryologia 62: 198–203.

Ilnicki T., Mitka J. 2011. Chromosome numbers in Aconitum sect. Cammarum (Ranunculaceae) from the Carpathians. Caryologia 64: 446–452.

Joachimiak A., Ilnicki T., Mitka J. 1999. Karyological studies on Aconitum lasiocarpum (Rchb.) Gáyer (Ranunculaceae). Acta Biol. Cracov., ser. Bot. 41: 205–211.

Kadota Y. 1987. A revision of Aconitum subgenus Aconitum (Ranunculaceae) in East Asia. Sanwa Shoyaku Company Ltd., Utsunomiya.

Kita Y., Ito M. 2000. Nuclear ribosomal ITS sequences and phylogeny of East Asian Aconitum subgen. Aconitum (Ranunculaceae), with special reference to extensive polymorphism in individual plants. Plant Syst. Evol. 225: 1–13.

Kita Y., Ueda K., Kadota Y. 1995. Molecular phylogeny and evolution of the Asian Aconitum subgen. Aconitum (Ranunculaceae). J. Plant Res. 108: 429–442.

Kluge A.G., Farris J.S. 1969. Quantitative phyletics and the evolution of anuras. Syst. Zool. 18: 1–32.

Liangqian L., Kadota Y. 2001. Aconitum L. In: Zhyengi W., Raven P.H., Deyuan H. (eds), Flora of China. Caryophylaceae through Lardizabalaceae. Vol. 6: 149–222. Science Press (Beijing), Missouri Botanical Garden (St. Louis).

Mai D. 1995. Tertiäre Vegetationsgeschichte Europas. G. Fischer Verl., Jena, Stuttgart, New York.

Mitka J. 2003. The genus Aconitum in Poland and adjacent countries – a phenetic-geographic study. Institute of Botany, Jagiellonian University, Kraków.

Mitka J., Sutkowska A., Ilnicki T., Joachimiak A. 2007. Reticulate evolution of high-alpine Aconitum (Ranunculaceae) in the Eastern Sudetes and Western Carpathians (Central Europe). Acta Biol. Cracov., ser. Bot. 49 (2): 15–26.

Müller K. 2005. SeqState-primer design and sequence statistics for phylogenetic data sets. Appl. Bioinformatics 4: 65–69.

Novikoff A., Mitka J. 2011. Taxonomy and ecology of the genus Aconitum in the Ukrainian Carpathians. Wulfenia 18: 37–61.

Novikoff A.V., Mitka J. 2015. Anatomy of stem-node-leaf continuum in Aconitum (Ranunculaceae) in the Eastern Carpathians. Nordic J. Bot. 33 (5): 633–640. doi: 10.1111/njb.00893

Pimentel M., Sahuquillo E., Torrecilla Z., Popp M., Catalán P., Brochmann Ch. 2013. Hybridization and long-distance colonization at different scales: towards resolution of long-term controversies in sweet vernal grass (Anthoxanthum). Ann. Bot. 112: 1015–1030.

Rannala B., Yang Z. 1996. Probability distribution of molecular evolutionary trees: A new method of phylogenetic inference. J. Mol. Evol. 43: 304–311.

Rieseberg L.H., Soltis D.E. 1991. Phylogenetic consequences of cytoplasmic gene flow in plants. Evol. Trends Plants 5: 65–84.

Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J.P., van der Mark P. 2005. MrBayes 3.1 Manual. San Diego: University of California at San Diego. http://mrbayes.sourceforge.net/wiki/index.php/Manual.

Sang T., Crawford D., Stuessy T. 1997. Chloroplast DNA phylogeny, reticulate evolution, and biogeography of Paeonia (Paeoniaceae). Am. J. Bot. 84 (8): 1120–1136.

Schönswetter P., Popp M., Brochmann C. 2006. Rare arctic-alpine plants of the European Alps have different migration histories: the snow bed species Minuartia biflora and Ranunculus pygmeus. Mol. Ecol. 15: 709–720.

Seitz W. 1969. Die Taxonomie der Aconitum napellus-Gruppe in Europa. Feddes Repert. 80 (1): 1–76.

Shaw J., Lickey E.B., Schilling E.E., Small R.L. 2007. Comparison of whole chloroplast genome sequences to choose non-coding regions for phylogenetic studies in angiosperms: the tortoise and the here III. Am. J. Bot. 94 (3): 275–288.

Simmons M.P., Ochoterena H. 2000. Gaps as characters in sequence-based phylogenetic analysis. Syst. Biol. 49: 369–381.

Skrede I., Eidesen P.B., Portela R.P., Brochman C. 2006. Refugia, differentiation, and postglaciation migration in arctic-alpine Eurasia, expemplified by the mountain avens (Dryas octopetala L.). Mol. Ecol. 15: 1827–1840.

Soltis D.E., Kuzoff R.K. 1995. Discordance between nuclear and chloroplast phylogenies in the Heuchera group (Saxifragaceae). Evol. 49: 727–742.

Starmühler W. 2001. Die Gattung Aconitum in Bayern. Ber. Bayer. Bot. Ges. 71: 99–118.

Swofford D.L. 2002. PAUP*. Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods). Version 4. Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, Massachusetts.

Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D, Filipski A., Kumar S. 2013. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30: 2725–2729.

Tiffney B.T. 1985. The Eocene North Atlantic land bridge: Its importance in Tertiary and modern phytogeography of the Northern Hemisphere. J. Arnold Arbor. 66: 243–273.

Utelli A.B., Roy B.A., Baltisbereger M. 2000. Molecular and morphological analyses of European Aconitum species (Ranunculaceae). Plant Syst. Evol. 224: 195–212.

Winkler M., Tribsch A., Schneeweiss G.M., Brodbeck S., Gugerli F., Holderegger R., Abbott R.J., Schönswetter P. 2012. Tales of the unexpected: phylogeography of the arctic-alpine model plant Saxifraga oppositifolia (Saxifragaceae) revisited. Mol. Ecol. 21 (18): 4618–4630. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2012.05705.x

Zając M., Zając A. 2009. The geographical elements of native flora of Poland. Laboratory of Computer Chorology, Institute of Botany, Jagiellonian University, Kraków.

Zhang Q., Feild S., Antonelli A. 2015. Assessing the impact of phylogenetic incongruence on taxonomy, floral evolution, biogeographical history, and phylogenetic diversity. Am. J. Bot. 102 (4): 566–580.

Zieliński R. 1982a. An electrophoretic and cytological study of hybridization between Aconitum napellus subsp. skerisorae (2n=32) and A. variegatum (2n=16). I. Electrophoretic evidence. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 51: 453–464.

Zieliński R. 1982b. An electrophoretic and cytological study of hybridization between Aconitum napellus subsp. skerisorae (2n=32) and A. variegatum (2n=16). II. Cytological evidence. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 51: 465–471.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The journal is licensed by Creative Commons under BY-NC-ND license. You are welcome and free to share (copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format) all the published materials. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. You must give appropriate credit to all published materials.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyrights and to retain publishing rights without any restrictions. This is also indicated at the bottom of each article.