Ovules anatomy of selected apomictic taxa from Asteraceae family

Abstract

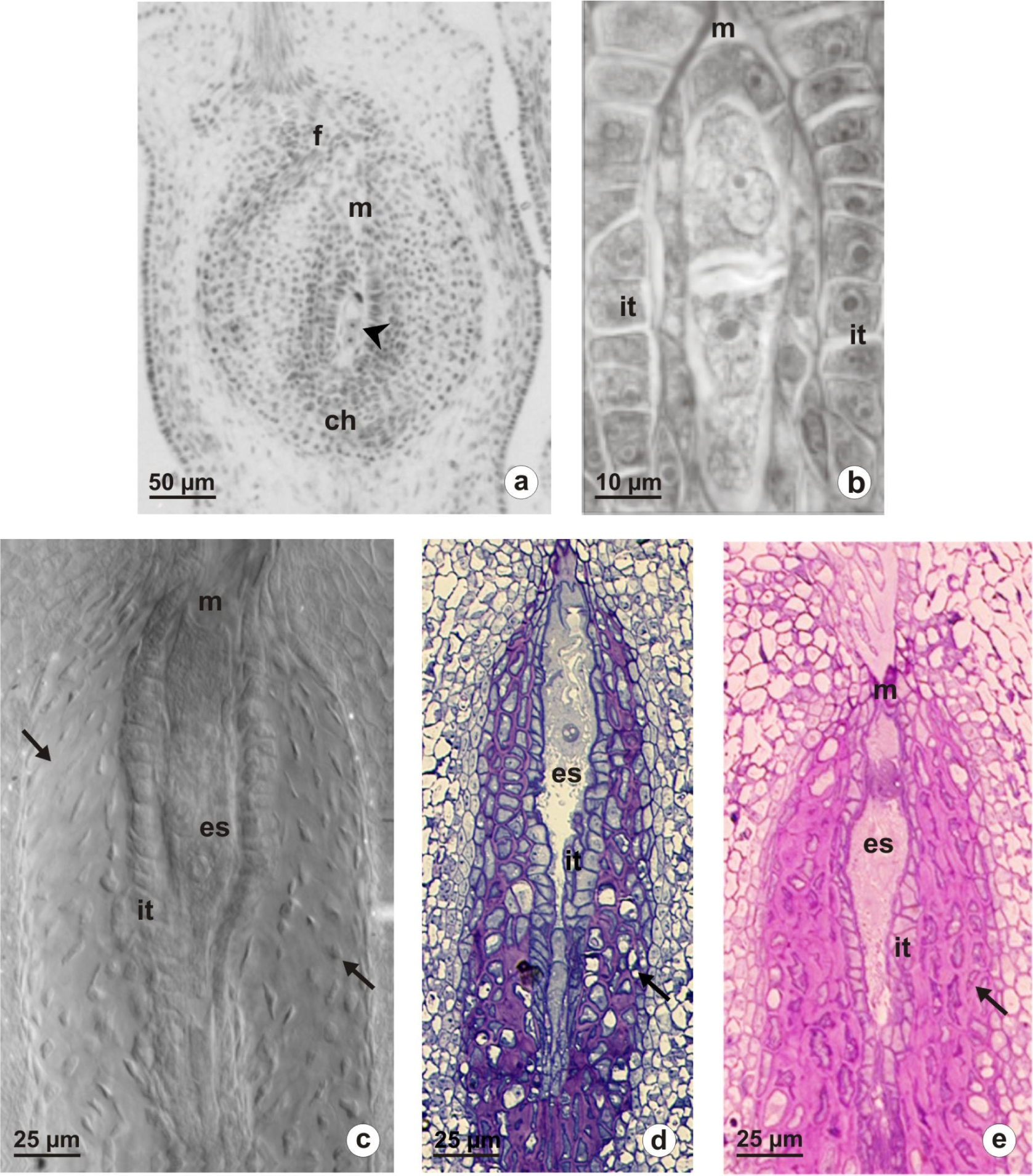

The present paper reports on our observations on the ovule structure of autonomous obligatory apomicts. We analyzed two triploid species of Taraxacum: T. udum, T. alatum and two triploid species of Chondrilla: Ch. juncea, Ch. brevirostris. The ovules of all studied species show a structure typical for the members of Asteraceae. One basal ovule develops into an inferior and unilocular ovary. The ovule is anatropous, tenuinucellate and unitegmic. Structural changes were observed in the ovule at the time of the embryo sac maturation. The innermost layer of integument develops into an endothelium surrounding the female gametophyte. Moreover, considerable modifications occurred in the integumentary cell layers adjacent to the endothelium. These cells show signs of programmed cell death and their walls begin to thicken. Histological analysis revealed that the prominent thick cell walls were rich in pectins. Layers of thick-walled cells formed a special storage tissue which, most likely, is an additional source of nutrients necessary for the proper nourishment of a female gametophyte and then of a proembryo.

References

Asker S.E., Jerling L. 1992. Apomixis in plants. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

Bicknell R.A., Bicknell K.B. 1999. Who will benefit from apomixis? Biotechnol. Dev. Monit. 37: 17–20.

Bicknell R.A. & Koltunow A.M. 2004. Understanding apomixis: recent advances and remaining conundrums. Plant Cell 16: 228–245.

Bhat V., Dwivedi K.K., Khurana J.P., Sopry S.K. 2005. Apomixis: An enigma with potential applications. Curr. Sci. 89: 1879–1893.

Carneiro V.T.C., Dusi D.M.A., Ortiz J.P.A. 2006. Apomixis: Occurrence, applications and improvements. In: Teixeira da Silva J.A. (ed.), Floriculture, ornamental and plant biotechnology: Advances and topical issues (1st Ed., Vol. I): 564–571. Global Science Books, Isleworth.

Johri B.M., Ambegaokar K.B., Srivastava P.S. 1992. Comparative embryology of Angiosperms. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

Kapil R.N., Tiwari S.C. 1978. The integumentary tapetum. Bot. Rev. 44: 457–490.

Koltunov A.M., Johnson S.D., Bicknell R.A. 1998. Sexual and apomictic development in Hieracium. Sex. Plant Reprod. 11: 213–230.

Koltunow A. 2000. The genetic and molecular analysis of apomixis in the model plant Hieracium. Acta Biol. Cracov., ser. Bot. 42: 61–72.

Kościńska-Pająk M. 2006. Biologia rozmnażania apomiktycznych gatunków Chondrilla juncea L., Chondrilla brevirostris L. i Taraxacum alatum Lindb. z uwzględnieniem badań ultrastrukturalnych i immunocytochemicznych. 1–104. KonTekst, Kraków. (in Polish).

Kościńska-Pająk M., Bednara J. 2006. Unusual microtubular cytoskeleton of apomictic embryo sac of Chondrilla juncea L. Protoplasma 227: 87–93.

Marciniuk J., Rerak J., Grabowska-Joachimiak A., Jastrząb I., Musiał K., Joachimiak A. 2010. Chromosome numbers and stomatal cell length in Taraxacum sect. Palustria from Poland. Acta Biol. Cracov., ser. Bot. 52: 117–121.

Musiał K., Płachno B.J., Świątek P., Marciniuk J. 2012. Anatomy of ovary and ovule in dandelions (Taraxacum, Asteraceae). Protoplasma DOI 10.1007/s00709-012-0455-x.

Noyes R.D. 2007. Apomixis in the Asteraceae: diamonds in the rough. Funct. Plant Sci. Biotechnol. 1: 207–222.

Noyes R.D. 2008. Sexual devolution in plants: apomixis uncloaked? Bioessays 30: 798–801.

Van Baarlen P., Verduijn M., Van Dijk P.J. 1999. What can we learn from natural apomicts? Trends Plant Sci. 4: 43–44.

Van Dijk P.J. 2003. Ecological and evolutionary opportunities of apomixis: insights from Taraxacum and Chondrilla. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 358: 1113–1121.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

The journal is licensed by Creative Commons under BY-NC-ND license. You are welcome and free to share (copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format) all the published materials. You may not use the material for commercial purposes. You must give appropriate credit to all published materials.

The journal allow the author(s) to hold the copyrights and to retain publishing rights without any restrictions. This is also indicated at the bottom of each article.